TL/DR

A Trust is a financial agreement between someone who owns an asset and a trusted person to hold and manage that asset for them. In estate planning, a Revocable Trust is often used as a substitute for a Will, but there are many other descriptions for any single Trust such as Irrevocable, Living, Joint, Testamentary, and Grantor. If you’re trying to unpack these terms and decide whether you should have a Trust in your estate plan, read this two-part article.

_________________________________________________________________

A Joint Trust, a Testamentary Trust, a Sub-Trust, a Revocable Trust (which sounds so much like “Irrevocable Trust” when said out loud)… There are so many adjectives used to describe Trusts, and it can quickly make your head spin. Once you dig deeper into these descriptive words for Trusts, you realize that many of these concepts come in pairs. Once you understand what feature of a trust is being described, and what the point of comparison is, it becomes much easier to understand the Trust’s use case.

This Article is divided into two parts. This Part 1 is a primer on the key differentiators between Trusts. Part 2 is a summary of the most commonly created Trusts in a foundational estate plan and their benefits.

Choosing to use a Trust in your estate plan is about being clear on your goals for how your assets should go to your loved ones. Trusts are created through a contract, and so there are a million different ways to write a contract to meet your specific goals.

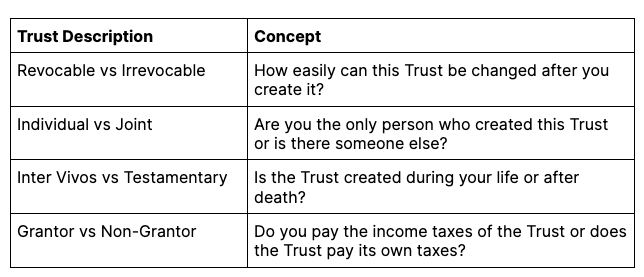

Here are the ways to describe a Trust that we will explore in this article:

Every term describes a different aspect of a Trust, and they are not mutually exclusive. In fact, every Trust can be described using one of the two choices from each category above. For example, if you use a Trust as a substitute for a Will in your foundational estate plan, you likely created a Revocable, Individual, Inter Vivos, Grantor Trust (most commonly shortened to “Revocable Trust”). If a Marital Trust will be created at your death, you will be creating an Irrevocable, Individual, Testamentary, Non-Grantor Trust. Let’s unpack each of these terms.

Revocable vs Irrevocable Trusts

The Revocable Trust, as the name implies, can be undone or unwound; the person who creates the Revocable Trust can simply “revoke” or “pull back” the Trust. The Irrevocable Trust, on the other hand, is much harder to change.

The Revocable Trust is often used as an alternative for a Will. It can also be used as an alternative to LLCs or Corporations to own an asset more privately while the owner is still alive.

The Irrevocable Trust is often used to give away assets while maintaining control over how the assets are used or to protect from specific types of taxes.

For most people, the introduction to Trusts begins with their own estate planning when they have to choose between making a Will or a Trust. In this context, the type of Trust you will be considering is the Revocable Trust (also commonly called a “Living Trust”).*2

Just as you would be able to change or completely revoke a Will (in many states, you could do this by ripping the original document!), you should be able to change or completely revoke your Revocable Trust. This is important because you could change your mind over the course of your life about key terms, such as who should get what asset. While you are alive and have mental capacity, you can easily change or revoke your Revocable Trust by signing a new Trust document.

An Irrevocable Trust is much harder to change, and it becomes especially difficult to remove or add beneficiaries or modify their individual rights. You might encounter this type of Trust even when creating your foundational estate plan (for example, a Marital Trust). In most states, once the Irrevocable Trust exists, changing this Trust requires the appointment of an independent trustee (if the Trust allows for it), the agreement of all the beneficiaries, or a court action. All of these options may be expensive and may require hiring an estate planner to do it right. For this reason, you must be certain you understand what powers and benefits you are giving up when you transfer property into an Irrevocable Trust.

That being said, Irrevocable Trusts are powerful vehicles for wealth transfer and preservation because you can control how the assets will be used. When properly structured, they provide protection against death taxes and creditors, which Revocable Trusts cannot do.

___

*This article is about different adjectives describing Trusts. To learn more about why you would want a Revocable Trust instead of a Will, check out the article.

*2 “Living” is also sometimes used interchangeably with “Inter Vivos” (see section on “Inter Vivos v. Testamentary Trusts”). But its most common use is to mean a Revocable Trust that is used as a substitute for a Will.

Individual vs Joint Trusts

An Individual Trust has one creator (called a “trustor,” “grantor,” or “settlor”), whereas a Joint Trust has two or more trustors. If you would like to create a Trust with someone else, be clear on why.

The most common reason to set up a joint trust is with your spouse. You already share in the management of the assets (e.g., you live in a community property state), file income taxes together, and share similar values, goals, and beneficiaries.

Income tax filings and payments may become messy if you and the other person are expected to report and pay the income taxes on the assets of the Trust (see “Grantor vs Non-Grantor Trust”) below.

For gift tax reasons (as well as introducing potential for complicated legal claims), you should also consider carefully giving your assets into a Trust that was created by someone else. For example, it may be tempting to give an inheritance to your nephew in a Trust that your parents set up for your nephew. It may be better for you to set up your own Trust to keep the Trust management straight-forward.

Inter Vivos vs Testamentary Trusts

Inter Vivos Trusts* are created during the trustor’s lifetime, whereas Testamentary Trusts are created only at the trustor’s death. This description is about the timing of when a Trust exists and can hold assets.

Inter Vivos Trusts allow the creator of the trust to transfer assets during life. Testamentary Trusts lie in wait until the creator has passed away and receive assets only then. The most common way to create a Testamentary Trust is to draft it into a Will or within another Trust (i.e., a “Sub-Trust”).

You may encounter both Inter Vivos and Testamentary Trusts when creating your foundational estate plan. For example, if you use a Revocable Trust as a substitute for a Will, you are creating an Inter Vivos Trust. In fact, it is important to transfer as much of your assets into this Trust during your life, if minimizing probate is important to you.

Your estate plan may also involve any number of Testamentary Trusts (created under your Will or your Revocable Trust) in order to specify how your assets can be used or given away after your death or to allow your loved ones to minimize future taxes. For example, you might set up a relatively short-lived Testamentary Trust called a “Holdback Trust” just so someone can help your child manage their financial affairs until your child is older.

____

*This term means “among the living” in Latin, and the English translation is “Living Trust.” However, the Living Trust is now commonly associated with Revocable Trusts used as a substitute for a Will, and so “Living” has become a confusing term because you can create an Irrevocable Trust during your life.

Grantor vs Non-Grantor Trusts

If you’ve made it this far in this article, you are really well on your way to understanding the features of a Trust that are important to an estate planner. Here is one more concept, which may matter more to your CPA. Your Trust may own assets that produce income (for example, real estate that is leased). It’s important to understand who is responsible for paying income taxes for Trust assets: you or the Trust.

A Grantor Trust does not pay its own taxes; another person (usually the Trust creator) must include the Trust’s income on his, her or its tax return and pay any income taxes. A Non-Grantor Trust pays its own taxes using the tax brackets for estates and trusts, which are different from the tax brackets for individuals.

Grantor Trusts retain enough of a connection to its “owner” (or “Grantor”) under the Tax Code so that the Grantor pays the taxes. Who is an owner is determined under a complex set of tax rules, and estate planners often intentionally turn on or turn off Grantor status on the Trust; but at a minimum, the owner must still be alive.

Having a Grantor trust is beneficial if you do not want to complicate tax reporting by having the Trust file a separate tax return or you want to treat the payment of taxes as an additional annual gift to your loved ones. In addition, a Non-Grantor Trust generally pays more income taxes than an individual taxpayer on the same amount of income. This is because the trust tax brackets are “compressed”; a Trust taxpayer reaches the maximum tax rate (i.e., 37%) at a lower income than does an individual taxpayer.

How does this concept apply to your foundational estate plan? If you use a Revocable Trust as a substitute for a Will, it will be a Grantor Trust that you “own” during your lifetime. A Revocable Trust does not result in any income tax savings: you must include the Trust’s income on your own tax return and pay those income taxes.

If you use a Sub-Trust (or Testamentary Trust) in your Will or Trust, that Trust will be created at your death and will usually be a Non-Grantor Trust. It will have to file and pay its own income taxes.

If you’re ready to get started creating a Revocable Trust follow this link.

To learn more about specific types of Trusts and their objectives, read Part 2 of this series.

Originally published January 24, 2023, and updated on November 14, 2025.